Peristalsis is the synchronized muscle contractions that push liquids and food throughout the intestinal tract. Primary peristalsis refers to the initial wave-like motion that occurs in the esophagus as you swallow, bringing food downwards toward the stomach.

Secondary peristalsis on the contrary is a backup mechanism that happens when liquid or food gets stuck or is reabsorbed into the esophagus. It is the coordinated contraction and relaxation of muscles in order to eliminate the obstruction, and to ensure proper digestion and flow through the digestive tract. Primary and secondary peristalsis play a vital role to ensure the proper operation of your digestive tract.

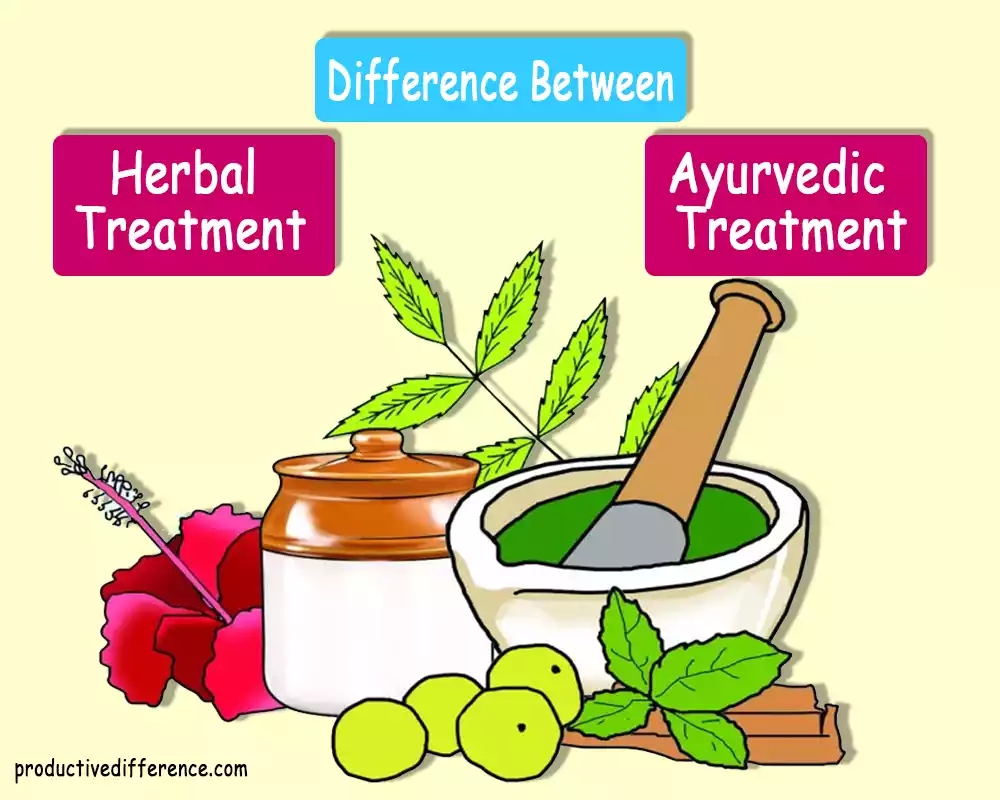

Definition of Primary Peristalsis

Primary peristalsis refers the controlled, sequential contractions of the esophageal muscle during swallowing. After you have swallowed, the action starts within the Pharynx (throat) and proceeds into the esophagus until it reaches the stomach. The swallowing process is voluntary and controlled by a neuronal circuit, called the swallowing centre located in the brainstem. It regulates the activity of different muscles in the throat as well as the esophagus.

Primary peristalsis’s purpose is to transport liquid bolus or food from the mouth, into the esophagus, before it goes to the stomach. It’s an essential element of digestion making sure that food and liquids are transported safely and efficiently through the food tract. The peristaltic motion is created by the continuous expansion and relaxing of the muscle layers within the esophagus, producing a wave-like motion which causes the bolus to descend.

Definition of Secondary Peristalsis

Secondary peristalsis is a series of muscle contractions within the esophagus, which occurs in spite of swallowing. Contrary to primary peristalsis that is triggered through swallowing food, secondary peristalsis may be caused due to the presence of leftover food particles or other irritants within the esophagus. This may occur when the primary peristaltic wave can not completely cleanse the esophagus of its contents or there is a reflux in stomach fluids back to the esophagus.

Secondary peristalsis is based on sensory receptors within the lining of the esophageal that recognize the existence of material that is not fully utilized. The receptors transmit signals through the esophageal nerves that then trigger the peristaltic waves that begin at the point of detection, and then moving downwards. This aids in clearing the esophagus and push any food particles or irritants that remain toward the stomach. Secondary peristalsis plays a vital protection mechanism that helps stop esophageal irritation and harm caused by long-term exposure to acidic or food-related gastric contents.

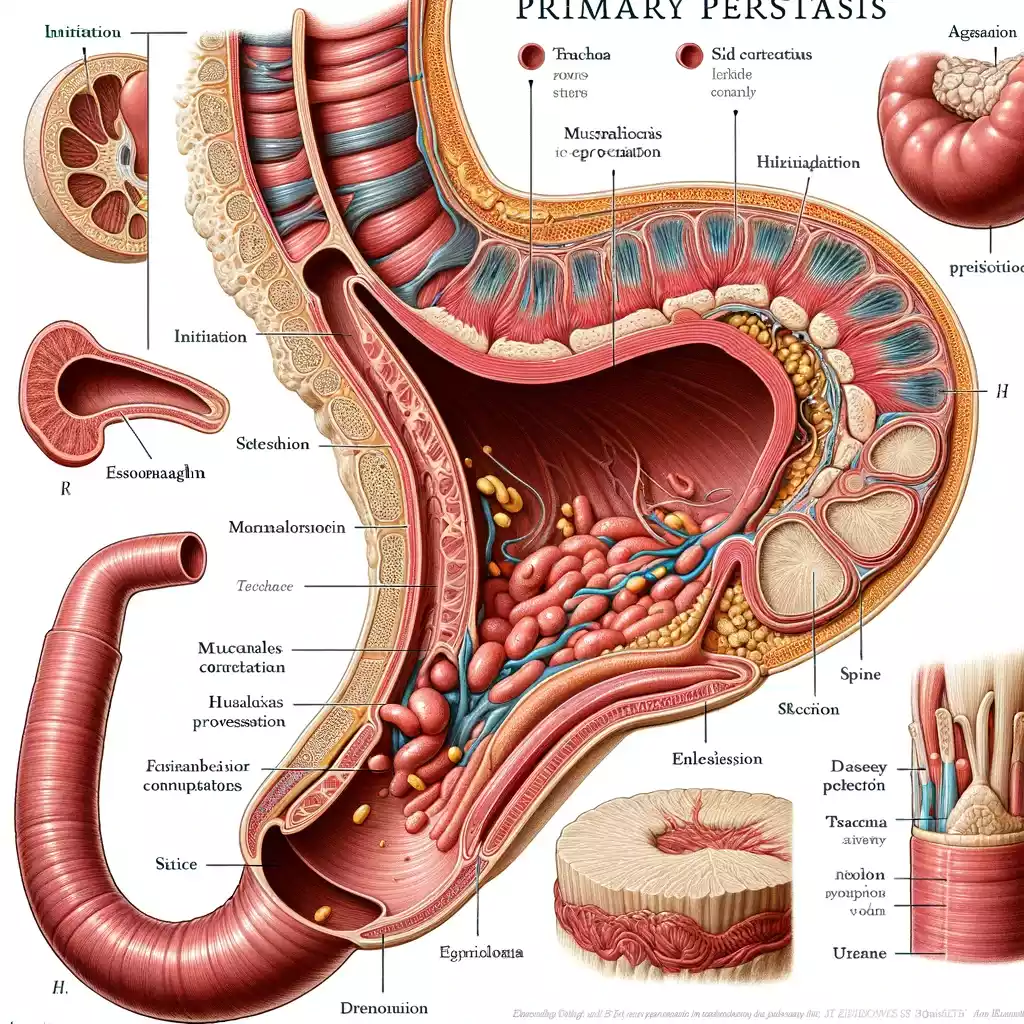

How does primary peristalsis work?

Primary peristalsis plays a crucial process within the digestive system, which ensures the smooth transfer of liquids and food between the stomach and mouth. This is how it works:

- Initialization with Swallowing: Primary peristalsis is initiated with swallowing. When you swallow this process, it begins by the pharynx (the back of the mouth).

- Neurological Coordination: The swallowing center in the brainstem region, specifically in the medulla Oblongata is a crucial part of controlling this process. It is activated upon swallowing and coordinates the movements of muscles necessary to perform peristalsis.

- Pharyngeal Stage: The material swallowed goes through the pharynx. In this stage, a series of muscle contractions that are coordinated shuts the nasal pharynx (to stop food particles from escaping into in the nasal cavities) as well as the larynx (to stop aspiration into lung).

- Esophageal stage: The bolus (the volume of liquid or food) is then absorbed into the esophagus. The upper esophageal muscle is relaxed to allow the bolus be able to enter, and then it contracts to stop air from entering the esophagus as well as food from re-entering the throat.

- Peristaltic Wave: When the bolus has been placed in the esophagus, a wave of muscle contractions push it downwards toward the stomach. The esophagus contains layers of muscles that contract sequentially and the circular muscles that surround the bolus contract to lower it and the longitudinal muscles that are ahead that of it contract in order to reduce the distance it must travel.

- Ingestion into the stomach: When the peristaltic wave is at the lower portion of the esophagus lower esophageal and sphincter (LES) relaxes allowing the bolus be absorbed into the stomach. Following the passage of the bolus, LES is again contracted to stop the reflux from stomach contents to the esophagus.

The entire primary peristalsis process typically lasts a couple of seconds and is crucial to allow the flow of liquid and food from the mouth into the stomach, helping further digestion. The process is simple and efficient, usually happening without conscious awareness.

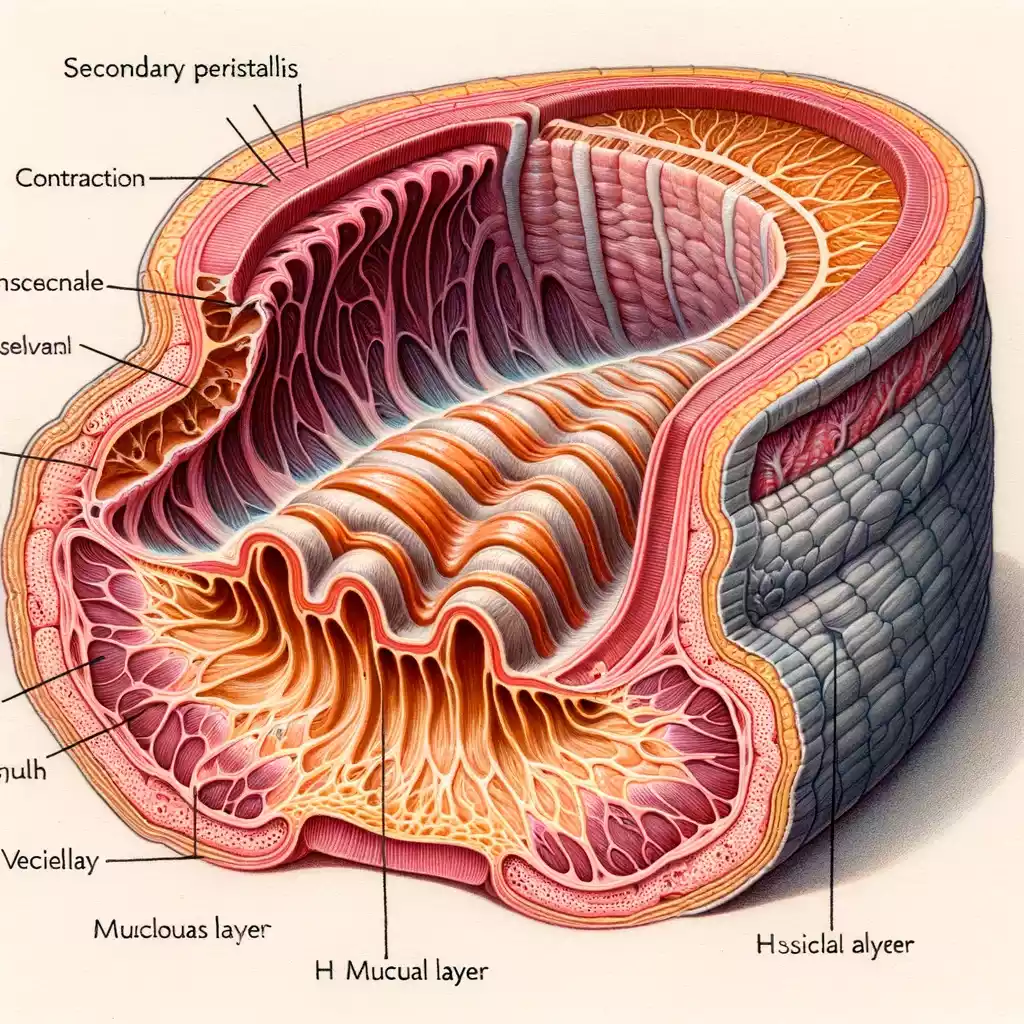

How does Secondary Peristalsis work?

Secondary peristalsis of the esophagus is an essential process to rid the esophagus from any remaining or refluxed matter that was not effectively moved by primary oristalsis. Here’s how it works

- Initiation through Sensory Detection: Secondary peristalsis started when sensory receptors within the lining of the esophagus detect liquids, food, or irritations (like stomach acids that have recirculated through the stomach into the stomach). This may occur following the initial peristaltic waves or on its own.

- The Neural Response: When these receptors are stimulated they transmit signals to esophageal nerves. In contrast to primary peristalsis which is controlled via the central nervous system, and initiated by swallowing, secondary or secondary peristalsis is caused by local reflex arcs inside the esophagus.

- Localized Peristaltic Waves: The neural signals cause the creation of a peristaltic wave that begins at the location of detection, not in the upper part of the esophagus as in the primary peristalsis. This provides a precise response to the location in which remnant material.

- Muscle Contractions: Like primary peristalsis, secondary is characterized by coordinated contractures of longitudinal and circular muscles of the esophagus. These muscles are contracted behind material that remains which pushes it down while the muscles that run longitudinally ahead of it contract to narrow the pathway.

- The process of clearing the Esophagus: Peristalstic waves help to move the leftover or refluxed matter down to the stomach. If the substance is not cleared in the first time, a secondary peristalsis could repeat itself until the esophagus has been cleared.

- Function within Esophageal Protection: Secondary peristalsis plays crucial roles as it protects the esophagus against injuries and irritation. By removing acidic or residual contents, it helps prevent prolonged exposure of the lining of the esophageal tract to substances that could cause inflammation or cause damage.

Secondary peristalsis is a natural and involuntary reaction, vital to maintaining the health of the esophagus and its function, particularly in cases when primary peristalsis is not effective or when reflux is a problem.

Comparison table of Primary and Secondary Peristalsis

Here’s a comparison table outlining the key differences between primary and secondary peristalsis:

| Aspect | Primary Peristalsis | Secondary Peristalsis |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger | Initiated by swallowing. | Triggered by the presence of residuals or irritants in the esophagus. |

| Purpose | To propel ingested food or liquid from the mouth through the esophagus to the stomach. | To clear the esophagus of residual food, liquid, or irritants, especially if the primary wave fails. |

| Control | Controlled by the swallowing center in the brainstem, as part of a reflex initiated by swallowing. | Initiated by sensory receptors in the esophageal lining that detect residual or refluxed materials. |

| Location of Initiation | Begins in the pharynx and continues down the esophagus. | Begins at the site of the residual material or irritation within the esophagus. |

| Involvement with Swallowing Process | Directly involved with the process of swallowing. | Not directly related to the act of swallowing; occurs independently. |

| Physiological Significance | Essential for the normal process of digestion, moving food to the stomach. | Acts as a protective mechanism to prevent esophageal irritation or damage. |

This table highlights the distinct roles and mechanisms of primary and secondary peristalsis in the esophagus. While primary peristalsis is a direct response to swallowing, secondary peristalsis serves as a corrective or protective response.

Similarities between Primary and Secondary Peristalsis

Peristalsis primary and secondary even though they differ in their beginning and goal, share some similarities.

- Esophageal muscle contractions: The two involve coordinated contractions of muscles of the esophagus. These are wave-like contractions that aid in transferring contents into the esophagus.

- Indispensable Processes: These two kinds of peristalsis are involuntary that is, they do not have conscious control. They are controlled through the nervous system of autonomic control.

- Function within Esophageal Clearance: The two roles serve the goal of transferring substances through the esophagus. Whether it’s liquids and food in normal swallowing (primary) or relics to protect against the esophagus from being damaged or irritated (secondary).

- The Sequential Muscle Activity: In both of the processes muscles contract in a sequence. This means that muscles stretch and relax within a coordinated manner to produce a wave-like motion which pushes the contents down the esophagus.

- Neural Pathways: Both kinds of peristalsis require intricate neural pathways that comprise motor and sensory neurons. These pathways assist in coordinating the activity of muscles essential to achieve peristalsis.

- The role of HTML0 in Digestive Process: Both primary and secondary peristalsis play an crucial to the digestion process, as they ensure that liquids, food and other esophageal substances are effectively moved to the stomach.

Understanding these commonalities is crucial to understand the way that the body sustains its esophageal functions and shields the esophagus against harm caused by the retention or reflux of materials.

Clinical Relevance

The clinical significance of peristalsis primary and secondary particularly in relation to diseases of the esophagus, is important. The understanding of these functions is essential to diagnose and manage different esophageal disorders:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disorder (GERD): In GERD stomach acid typically is absorbed into the esophagus creating inflammation and irritation. The ability to perform a secondary peristalsis effectively is vital in the elimination of acid reflux and decreasing the risk of developing the esophagitis (inflammation of the stomach) and complications such as Barrett’s esophagus.

- Achalasia: It is a disorder in which the lower esophageal muscle fails to relax properly when swallowing, causing difficulties in food passing from the esophagus into the stomach. In this case, disruption of normal peristalsis may cause severe symptoms, such as dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) regurgitation, dysphagia and chest pain.

- Esophageal dysmotility disorders: Conditions such as diffuse esophageal spasms or ineffective Esophageal motility are characterized by irregular peristaltic movements. These conditions can cause symptoms like dysphagia, chest pain, and regurgitation. Peristalsis knowledge can help diagnose the conditions by using techniques such as manometry of the esophageal region.

- Esophageal Obstruction or Stricture: Conditions that cause narrowing of the esophagus could hinder regular flow liquids and food. Peristalsis can be clinically significant in these cases, since it can either cause symptoms to worsen by causing a forceful contraction against obstruction, or it could not be effective due to an esophagus that is narrower.

- Aspiration Risk: A lack of esophageal clearance regardless of the cause, such as poor primary peristalsis or insufficient secondary peristalsis can increase the chance of aspiration particularly in those with neurological disorders or difficulty swallowing.

- Evaluation of Esophageal Function: Tests such as manometry of the esophagus, which measures the changes in the pressure of the esophagus when peristalsis is occurring is essential to evaluate the function of the esophagus. These tests can aid in identifying irregularities in peristaltic movement which could be the cause of symptoms.

- Impacts of Treatment: Understanding the peristalsis process is essential for the management of esophageal problems. For instance, prokinetic medications can increase peristaltic function, while other treatments might concentrate in relaxing the esophageal muscle or decreasing reflux.

Primary and second peristalsis aren’t just essential to the normal functioning of the esophageal tract, but are also a major factor in the pathophysiology of a variety of diseases of the esophageal tract. Their knowledge aids with the identification, treatment and therapy of such disorders.

Disorders related to peristalsis

A variety of disorders are directly connected to the abnormalities in esophageal peristalsis. These conditions can severely impact the normal functioning of the esophagus. They can also cause a variety of symptoms.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disorder (GERD): While GERD is mostly due to the refluxing of stomach contents back into the esophagus an impaired peristalsis may aggravate the symptoms. Inadequate clearance of the esophagus as a result of weak peristaltic waves could delay the exposure of the esophageal tissue to acidic contents which can cause inflammation and irritation.

- Achalasia: Achalasia is a motility disorder in which the lower esophageal and sphincter (LES) does not relax properly during swallowing it results in a decrease in peristaltic waves within the esophageal organs. Achalasia sufferers have difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) as well as regurgitation and, in most cases, chest discomfort.

- Dispersive Esophageal Spasm: It is defined by strong or uncoordinated constriction of the stomach. this condition may cause discomfort in the chest and difficulties swallowing. The peristaltic waves are not uniform and usually occur in a series instead of in a sequential fashion, causing disruption to normal esophageal movement.

- Scleroderma as well as Systemic Sclerosis: The immune-mediated diseases can impact the smooth muscle of the esophagus that can cause a reduction in the peristaltic function. This could result in severe dysphagia, as well as an increased risk of GERD because of the poor clearance of the esophagus.

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): EoE is an inflammation-related condition frequently triggered by allergens. It can result in changes in the esophageal esophagus’ peristalsis structure, causing dysphagia as well as food impaction.

- Effective Esophageal Motility (IEM): IEM is characterised by weak or insufficient peristaltic waves that can hinder the effective flow of food through the esophagus. It can trigger symptoms that are similar to GERD such as heartburn and regurgitation.

- Nutcracker Esophagus: The reason for this is that in the situation the peristaltic muscles of the esophagus are too powerful (hypercontractile) which can cause chest discomfort and dysphagia.

- Esophageal Rings and Strictures: Although they are structural issues they may impair peristalsis through physical obstruction to the passage of food causing dysphagia symptoms and even regurgitation.

- Neurological disorders: Disorders like Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease or stroke may impact the nerves that control the peristalsis of the esophageal lining, causing dysphagia, as well as other esophageal motility issues.

In all these situations it is evident that the normal pattern as well as the strength of muscles contractions are affected which can result in a myriad of symptoms, and impacting the quality of living. Diagnostic tests are often conducted to determine the esophageal motility and treatment depends on the root cause and the severity of the condition.

Managing Peristalsis-Related Disorders

Managing peristalsis-related disorders involves a combination of diagnostic evaluation, medical therapy, dietary modifications, and sometimes surgical interventions:

- Diagnostic Evaluation: This typically involves esophageal manometry to assess the strength and coordination of esophageal contractions and pH monitoring to evaluate for acid reflux. Endoscopy may also be used to visualize the esophagus and identify structural abnormalities.

- Medical Therapy: This can include proton pump inhibitors for acid suppression in GERD, prokinetic agents to enhance peristalsis, and muscle relaxants for spasmodic disorders.

- Dietary Modifications: Smaller, more frequent meals and avoidance of trigger foods can help reduce symptoms. Patients are often advised to eat slowly and chew thoroughly to aid the process of swallowing and peristalsis.

- Surgical Interventions: In cases like achalasia or severe GERD, surgical options may include procedures like Heller myotomy, fundoplication, or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). These surgeries aim to correct functional abnormalities at the esophageal sphincter or enhance esophageal clearance.

- Lifestyle Changes: Weight management, avoiding lying down immediately after eating, and elevating the head of the bed can help manage reflux symptoms.

- Monitoring and Follow-up: Regular follow-up is important to monitor the progression of the disorder and the effectiveness of treatment strategies.

Each patient’s management plan is tailored based on the specific disorder, its severity, and the individual’s overall health and symptoms.

Recent Advances in Peristalsis Research

Recent advances in peristalsis research, particularly relating to esophageal motility disorders, highlight the ongoing efforts to better understand and treat these conditions:

- Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE-5) Inhibitors and Esophageal Motility: A study systematically reviewed the effects of PDE-5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil, on esophageal motility. These drugs are known to induce smooth muscle relaxation and have been proposed as a treatment option for disorders like achalasia. The study, which included 14 different studies conducted in various countries, found that PDE-5 inhibitors significantly reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure and the amplitude of contractions. This suggests that these drugs may be beneficial in treating esophageal motility disorders, offering symptom relief and potentially preventing associated complications. However, larger studies are needed to establish definitive evidence regarding their efficacy.

- Esophageal Motility Disorders in Relation to Age: Another study focused on the relationship between esophageal motility disorders and age. This research, which involved conventional esophageal manometry performed on 385 symptomatic patients, found that about one-third of the patients had achalasia, with higher manometric results in patients over 65 compared to those under 65. The study concluded that achalasia is a prevalent cause of dysphagia in elderly patients, increasing their risk of malnutrition and functional impairment. This underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in treating older patients with these disorders.

- Age-Related Changes in Esophageal Motility: Studies have shown that aberrant esophageal motility is more common with age. Healthy adults over 75 have exhibited decreased basal lower esophageal sphincter tone and an increased mean integrated relaxation pressure. Age-related structural and functional changes in the esophagus can lead to motility abnormalities, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life by leading to issues like malnutrition and increased vulnerability to other health problems. In older individuals, a decrease in the percentage of swallows accompanied by complete LES relaxation may result in ineffective esophageal motility, even if the overall esophageal function remains intact.

These studies highlight the importance of ongoing research in understanding esophageal motility disorders, their relation to factors like age, and the potential for novel treatments to improve patient outcomes. The findings emphasize the need for targeted therapeutic strategies, especially in vulnerable populations like the elderly.

Final Opinion

Primary and secondary peristalsis are critical mechanisms in the esophagus for transporting food and liquids to the stomach. Primary peristalsis is initiated by swallowing and involves a coordinated wave of muscular contractions that propel the food bolus from the mouth to the stomach. Secondary peristalsis, on the other hand, is triggered not by swallowing but by the presence of residual food or irritants in the esophagus.

It helps in clearing any remaining material, thus protecting the esophageal lining from damage. Both processes are essential for normal esophageal function, with primary peristalsis facilitating digestion and secondary peristalsis acting as a protective mechanism against irritation and injury.